After my first maniraptor movie review, Babbletrish suggested that I should do one on Happy Feet. I had not seen Happy Feet at the time, but, eventually, I did. Spoilers ahead!

I'm going to agree that seeing otherwise realistic penguins with human-like eyes and dancing like humans is rather... uncanny. I'm not someone who cares that much about graphics or whatever, so that alone might not have put me off this movie. But, truth be told, I felt that the other aspects of the movie were rather "meh". That, and I also thought the ending was slightly rushed and not all that believable. Why would a zoo just suddenly release a new animal celebrity back to the wild? How did the humans figure out that the penguins were trying to communicate with them and what they were trying to say? It's as though someone just put that forth as a random suggestion and everyone else just went, "Hey, let's go with that!" The one mildly interesting thing I found in this movie was how Carnivore Confusion was treated. For a moment you might think the leopard seal is a mindless movie monster, and then it talks. Strangely, the orcas of all things are the only animals (besides actinopterygians and humans, naturally) that don't display an ability to communicate with the rest of the cast.

For all its faults, I must confess that, tap dancing aside, this movie has penguin biology down rather well. Emperor penguins really do sing during courtship, and the males really do huddle together for months while incubating the eggs. (Though just so you know, real emperor penguins sound like this.) Also, penguins really do jostle for position when entering the water as a way of checking for predators. Adélie penguins really are plucky birds, and really do offer stones to potential mates. On the other hand, unlike emperor penguins, Adélie penguins don't breed on the ice, even though they live on it for most of the year. A lone Eudyptes penguin (I do not know exactly which species, if any, it's supposed to represent; I'm guessing one of the rockhopper penguins) also shows up in this movie. Eudyptes penguins are usually found on the subantarctic islands surrounding Antarctica instead of the ice, but given that this is just one individual I assume he's a special case. Some skuas get a few brief scenes (though I am, again, unable to identify their precise species), and from what little we see of them they appear to be portrayed fairly accurately.

Finally, this has nothing to do with maniraptors, but the elephant seals are implied to be herbivores. Really? Unless this was meant as a joke that never gets corrected in the film, it sounds like someone got way too caught up in the similarities between elephant seals and elephants.

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Friday, June 24, 2011

Maniraptor Feathers Part VII: Are Feathered Maniraptors, Like, Totally Uncool?

This will be the last post in this series for now.

I suppose it can be said that many objections to feathered maniraptors, however flawed, have at least some apparent basis to them. But all too often I see arguments that have zero reasoning behind them, arguments that amount to little more than, "I refuse to believe maniraptors had feathers" or "I don't like how feathered maniraptors look."

I don't think I even need to explain how wrong this kind of "argument" is. They're entirely subjective, for starters. My two cents on the issue? These look terrible.

Or, to quote Babbletrish, "Naked maniraptors look stupid."

More importantly, organisms living millions of years ago don't care what a few individuals of one freaking species think. There's nothing wrong with liking naked maniraptors, but how that influences the characteristics of real-life animals is beyond me. I am completely incapable of seeing why this concept is so difficult to grasp.

I suppose it can be said that many objections to feathered maniraptors, however flawed, have at least some apparent basis to them. But all too often I see arguments that have zero reasoning behind them, arguments that amount to little more than, "I refuse to believe maniraptors had feathers" or "I don't like how feathered maniraptors look."

I don't think I even need to explain how wrong this kind of "argument" is. They're entirely subjective, for starters. My two cents on the issue? These look terrible.

Or, to quote Babbletrish, "Naked maniraptors look stupid."

More importantly, organisms living millions of years ago don't care what a few individuals of one freaking species think. There's nothing wrong with liking naked maniraptors, but how that influences the characteristics of real-life animals is beyond me. I am completely incapable of seeing why this concept is so difficult to grasp.

Maniraptor Feathers Part VI: Lizard-faced Monsters in Gorilla Suits

It is abundantly clear by now that all evidence points to the fact that non-avian maniraptors had feathers, and most objections to such are little more than attempts to cover up desperate denial that hold little weight if any. A common problem in serious reconstructions of extinct maniraptors these days is not that they lack feathers, but that they aren't feathered correctly.

As Andrea Cau puts it (after being garbled by Google Translate), many depictions of "feathered dinosaurs" don't actually depict "feathered dinosaurs" but "dinosaurs with feathers". They don't really show how these dinosaurs were feathered in life, but take a traditional scaly dinosaur and stick it in a suit of feathers. In other words, they're the equivalent of sticking a human into a gorilla suit and calling it a gorilla. I don't remember where I heard that analogy first, but it sounds apt to me.

It's not just non-avian maniraptors. Even the de facto "first bird" Archaeopteryx runs into this problem a lot. In reality, we have a decent amount of data on the plumage of these dinosaurs, and they certainly weren't scaly dinosaurs stuck in feathered suits. I briefly described in Part I what we presently know about the plumage of each non-avialian maniraptor for which evidence of feathers has been found. Incidentally, at least one thing I said in Part I is now probably outdated. I talked about how protofeathers, plumaceous feathers, and pennaceous feathers are all known in maniraptors. That is still true, but not in the way I described. A new study has shown that the feathers preserved in the feathered dinosaur specimens are likely more complex than typically thought. A (dead) European siskin was crushed in a printing press to simulate the preservation of the feathered dinosaur specimens, and it turned out that crushed pennaceous body feathers looked like plumaceous feathers or protofeathers. So the "protofeathers" and "plumaceous feathers" found on the bodies of oviraptorosaurs, deinonychosaurs, and basal avialians are likely actually pennaceous feathers, and the protofeathers in more basal maniraptors and other coelurosaurs are probably plumaceous feathers, or at least multiple filaments joined together at the base instead of single filaments. That leaves only the bristle-shaped EBFFs found in Beipiaosaurus (and possibly some undescribed basal coelurosaur taxa) as the only known monofilament feathers in maniraptors. Incidentally, the "ribbon-shaped" wing feathers reported in the juvenile Similicaudipteryx are likely just developing regular pennaceous feathers, while the ribbon-shaped tail feathers in many Mesozoic birds really are ribbon shaped, but the ribbon-shaped part is probably a specialized calamus instead of fused barbs as usually interpreted.

Several common and persistent characteristics of gorilla suit dinosaurs routinely find their way into reconstructions, even those that are otherwise perfectly accurate. Inaccurate wing feathers are one. All modern birds have a fairly uniform wing feather arrangement: tertials attaching to the humerus, secondaries attaching to the ulna, and primaries attaching to the second finger. Non-avian maniraptors and basal avialians don't appear to have had tertials, but aside from that all evidence so far shows that oviraptorosaurs and deinonychosaurs had a similar wing feather arrangement. Other than Caudipteryx zoui and the juveniles of Similicaudipteryx, all oviraptorosaurs and deinonychosaurs with preserved wing feathers have secondaries, and all, so far without exception, have primaries. (More basal maniraptors, such as therizinosaurs, didn't have actual wing feathers, just long protofeathers on the arms.) Possibly by far the most common error in depictions of plumage in oviraptorosaurs and deinonychosaurs is the lack of primary feathers. Although some speculate that certain taxa might have lost the primary feathers, this is typical wishful thinking. There is no evidence that this was the case. Even in flightless birds with short, stubby forelimbs, primary feathers remain, though they aren't easy to see because they "blend in" with the body feathers. Nor is there any reason to suppose that wing feathers would have gotten in the way of catching prey, as the palms and claws of theropods do not point the same way as the feathers do. On a related note, there is no evidence that the fingers of deinonychosaurs were scaly, even though just about everyone reconstructs them that way. As far as we know, even the fingers of deinonychosaurs were fuzzy, although oviraptorosaurs on the other hand appear to have had scales or naked skin on their fingers.

Another common error in reconstructions of feathered dinosaurs is stopping the head feathers at the snout, or worse, having scaly, lizard-like heads. Most of these reconstructions are evidently inspired by the fact that in modern birds, feathers stop at the snout. However, modern birds have beaks. In beakless maniraptors (including many Mesozoic birds), the feathers appear to go all the way down the snout, leaving only some naked skin at the tip. Of course, there are variations on this. Beipiaosaurus appears to have had a naked face, and many modern bird clades have evolved naked faces. Even so, there is no reason think that any maniraptor re-evolved scales on previously feathered parts of the body, even if they might have secondarily lost their facial feathers. By the way, although it is common to speculate that carnivorous non-avian maniraptors had bald heads, this appears to be based on vultures, and as I discussed briefly in Part V, bald heads in vultures have more to do with soaring habits than with feeding behavior.

Finally, in paleo art, it's common practice to "show all work" and make sure all the skeletal features and proportions of a dinosaur can been seen in reconstructions. However, as Matt Martyniuk, Mickey Mortimer, and Dr. Darren Naish discuss in the comments here, restoring feathered dinosaurs means "obscuring your research". Just look at how much feathers can cover up skeletal features in modern birds! Fossils of non-avian maniraptors also show obscuring of skeletal features by plumage. (Take a look at the fossils of "Dave" or Beipiaosaurus I posted back in Part I.) Even in featherless dinosaurs, the presence of soft tissues would mean that they were far from the shrink-wrapped creatures commonly depicted in art.

As Andrea Cau puts it (after being garbled by Google Translate), many depictions of "feathered dinosaurs" don't actually depict "feathered dinosaurs" but "dinosaurs with feathers". They don't really show how these dinosaurs were feathered in life, but take a traditional scaly dinosaur and stick it in a suit of feathers. In other words, they're the equivalent of sticking a human into a gorilla suit and calling it a gorilla. I don't remember where I heard that analogy first, but it sounds apt to me.

|

| This is supposed to be a chicken. |

It's not just non-avian maniraptors. Even the de facto "first bird" Archaeopteryx runs into this problem a lot. In reality, we have a decent amount of data on the plumage of these dinosaurs, and they certainly weren't scaly dinosaurs stuck in feathered suits. I briefly described in Part I what we presently know about the plumage of each non-avialian maniraptor for which evidence of feathers has been found. Incidentally, at least one thing I said in Part I is now probably outdated. I talked about how protofeathers, plumaceous feathers, and pennaceous feathers are all known in maniraptors. That is still true, but not in the way I described. A new study has shown that the feathers preserved in the feathered dinosaur specimens are likely more complex than typically thought. A (dead) European siskin was crushed in a printing press to simulate the preservation of the feathered dinosaur specimens, and it turned out that crushed pennaceous body feathers looked like plumaceous feathers or protofeathers. So the "protofeathers" and "plumaceous feathers" found on the bodies of oviraptorosaurs, deinonychosaurs, and basal avialians are likely actually pennaceous feathers, and the protofeathers in more basal maniraptors and other coelurosaurs are probably plumaceous feathers, or at least multiple filaments joined together at the base instead of single filaments. That leaves only the bristle-shaped EBFFs found in Beipiaosaurus (and possibly some undescribed basal coelurosaur taxa) as the only known monofilament feathers in maniraptors. Incidentally, the "ribbon-shaped" wing feathers reported in the juvenile Similicaudipteryx are likely just developing regular pennaceous feathers, while the ribbon-shaped tail feathers in many Mesozoic birds really are ribbon shaped, but the ribbon-shaped part is probably a specialized calamus instead of fused barbs as usually interpreted.

Several common and persistent characteristics of gorilla suit dinosaurs routinely find their way into reconstructions, even those that are otherwise perfectly accurate. Inaccurate wing feathers are one. All modern birds have a fairly uniform wing feather arrangement: tertials attaching to the humerus, secondaries attaching to the ulna, and primaries attaching to the second finger. Non-avian maniraptors and basal avialians don't appear to have had tertials, but aside from that all evidence so far shows that oviraptorosaurs and deinonychosaurs had a similar wing feather arrangement. Other than Caudipteryx zoui and the juveniles of Similicaudipteryx, all oviraptorosaurs and deinonychosaurs with preserved wing feathers have secondaries, and all, so far without exception, have primaries. (More basal maniraptors, such as therizinosaurs, didn't have actual wing feathers, just long protofeathers on the arms.) Possibly by far the most common error in depictions of plumage in oviraptorosaurs and deinonychosaurs is the lack of primary feathers. Although some speculate that certain taxa might have lost the primary feathers, this is typical wishful thinking. There is no evidence that this was the case. Even in flightless birds with short, stubby forelimbs, primary feathers remain, though they aren't easy to see because they "blend in" with the body feathers. Nor is there any reason to suppose that wing feathers would have gotten in the way of catching prey, as the palms and claws of theropods do not point the same way as the feathers do. On a related note, there is no evidence that the fingers of deinonychosaurs were scaly, even though just about everyone reconstructs them that way. As far as we know, even the fingers of deinonychosaurs were fuzzy, although oviraptorosaurs on the other hand appear to have had scales or naked skin on their fingers.

Another common error in reconstructions of feathered dinosaurs is stopping the head feathers at the snout, or worse, having scaly, lizard-like heads. Most of these reconstructions are evidently inspired by the fact that in modern birds, feathers stop at the snout. However, modern birds have beaks. In beakless maniraptors (including many Mesozoic birds), the feathers appear to go all the way down the snout, leaving only some naked skin at the tip. Of course, there are variations on this. Beipiaosaurus appears to have had a naked face, and many modern bird clades have evolved naked faces. Even so, there is no reason think that any maniraptor re-evolved scales on previously feathered parts of the body, even if they might have secondarily lost their facial feathers. By the way, although it is common to speculate that carnivorous non-avian maniraptors had bald heads, this appears to be based on vultures, and as I discussed briefly in Part V, bald heads in vultures have more to do with soaring habits than with feeding behavior.

| Fossil of Eoenantiornis buhleri showing feathered snout photographed by Laikayiu, from Wikipedia. |

Finally, in paleo art, it's common practice to "show all work" and make sure all the skeletal features and proportions of a dinosaur can been seen in reconstructions. However, as Matt Martyniuk, Mickey Mortimer, and Dr. Darren Naish discuss in the comments here, restoring feathered dinosaurs means "obscuring your research". Just look at how much feathers can cover up skeletal features in modern birds! Fossils of non-avian maniraptors also show obscuring of skeletal features by plumage. (Take a look at the fossils of "Dave" or Beipiaosaurus I posted back in Part I.) Even in featherless dinosaurs, the presence of soft tissues would mean that they were far from the shrink-wrapped creatures commonly depicted in art.

|

| Museum mount of Strix nebulosa showing extent of plumage, photographed by FunkMonk, from Wikipedia. |

Wednesday, June 22, 2011

Maniraptor Feathers Part V: What About Big Maniraptors?

The idea that some extinct maniraptors may have secondarily lost their feathers because "they didn't need them" is one that currently has no evidence for, and in most cases comes from the ignorance of the vast potential functions that feathers have. However, there is one instance where this line of reasoning does at least appear to make sense, and that is when big maniraptors are concerned.

How big is a big maniraptor? Some would say Deinonychus was a "big maniraptor", but truth be told it really... wasn't. Although it was fairly large for a dromaeosaurid, it still wasn't larger than even the largest living maniraptor, the ostrich. A large ostrich can easily weigh more than a hundred kilograms, while Deinonychus has been estimated at around seventy kilograms.

There are several dromaeosaurids that were much larger than Deinonychus, however. Achillobator, Austroraptor, and Utahraptor are the largest dromaeosaurids known. Utahraptor has been estimated at five hundred kilograms and seven meters long, and Achillobator and Austroraptor were probably slightly smaller. Some rumored undescribed specimens of Utahraptor are allegedly even larger, but for the sake of simplicity we can probably ignore those for now.

Large as they were, these large dromaeosaurids were dwarfed by several other maniraptors. The oviraptorosaur Gigantoraptor was more than eight meters long and weighed more than a ton. It was about the same size as the tyrannosaurids Albertosaurus and Gorgosaurus. Multiple therizinosaur taxa may have also rivaled or exceeded the biggest dromaeosaurids in mass, including Alxasaurus, Falcarius, Nothronychus, Suzhousaurus, Enigmosaurus, Erlikosaurus, Nanshiungosaurus, and Segnosaurus. The largest known therizinosaur (in fact, the largest known maniraptor) was Therizinosaurus itself. Some estimates put it as being around three meters tall at the hip and weighing as much as six tons. Given the strange, upright build therizinosaurs tended to have, it probably would've been a very imposing animal in life.

The concept that large maniraptors may have lost their feathers is based on the fact that several large modern tropical land mammal lineages (such as elephants, rhinos, and hippos) have greatly reduced insulating integument, which sounds reasonable. (It's a bit less reasonable when other types of mammals such as humans, naked mole rats, or whales are brought up, given that their reduction of hair involves specialized lifestyles not known in any maniraptor.) These mammals have dispensed with a thick coat of hair because they are large enough to maintain their body temperature without insulation, and probably because they'd overheat with a typical mammalian coat.

On the other hand, there's reason to think that overheating was not quite as much of a problem for theropods as it is for mammals. For one thing, theropods typically have greater surface to volume ratio than mammals do. After all, Velociraptor was roughly the size of a coyote, but was longer than the average man is tall. Even among mammals, surface area to volume ratio appears to make a difference in determining how much insulating integument is reduced. Giraffes and black rhinos are in the same size range, but giraffes haven't greatly reduced their coats of hair, because their surface area to volume ratio is much greater than that of black rhinos. It's worth noting that the builds of elephants, hippos, and rhinos are all terrible for shedding heat, while this was not the case with theropods. Secondly, theropods have an air sac system that mammals do not, and greatly increases their ability to shed excess heat. Indeed, preliminary calculations by Andrea Cau suggest that not even the tyrannosaurid Tyrannosaurus would've been greatly inconvenienced by a feather coat, and Tyrannosaurus was significantly larger than all known maniraptors, barring Therizinosaurus. I suspect the largest coelurosaur with a coat of plumage of a given thickness would've potentially been larger than the largest mammal with an equally thick hair coat.

Besides, there are other reasons why elephants, hippos, and rhinos don't make ideal comparisons to most big maniraptors. Rumors notwithstanding, Utahraptor, Achillobator, and Austroraptor weren't anywhere close to the size of those big mammals. Modern mammals in their size range, even those in tropical environments, don't show a particularly marked reduction in hair. (Funnily, the largest known avian maniraptors were about as large as the largest dromaeosaurids, but rarely does anyone suggest that they lost their feathers. Such baseless differences between the treatment of non-avian and avian maniraptors is quickly becoming an Overly Long Gag.) That leaves only Gigantoraptor, Nothronychus, Suzhousaurus, Segnosaurus, and Therizinosaurus as the only known maniraptors in the size range of large terrestrial mammals with reduced integument covering. Furthermore, the hair loss in hippos (and likely the ancestors of elephants) may well have as much to do with their semi-aquatic habits as it does with size and build, while there's no evidence that any big maniraptors had semi-aquatic ancestors.

There's more. Feathers, especially pennaceous feathers (which most maniraptors have) are excellent insulators. They prevent both heat loss from the body and overheating caused by ambient heat. We're biased in our typical view of insulation because we deal with high temperatures by sweating, which isn't too effective with thick clothing covering our skin, but in fact, male turkeys are more likely to overheat from high ambient temperatures than female turkeys are because of their bald heads. Even for us, wearing thin clothing that still allows for evaporation of sweat can actually help lower body temperature. That said, feather loss in some areas of the body in maniraptors can be beneficial under some circumstances. For example, ostriches have naked flanks, legs, and inner wings, and rheas have naked legs and inner wings. These birds can run very fast and probably generate a lot of heat doing so, but live in fairly arid environments and can remain active in hot weather. It turns out that the featherless parts of an ostrich or rhea can all be shaded easily by the bird's wings or the rest of the body, so the heat generated during the day is stored and then can be rapidly shed in one go. The bald heads of certain vultures have also been found to be important in thermoregulation (instead of being an adaptation to cope with messy feeding habits; indeed, the messiest vultures don't have the baldest heads, and most vultures have feathered heads). These vultures usually need to cope with rapidly changing temperatures while soaring, and can quickly facilitate or prevent heat loss by extending or retracting the neck. Even the bald heads of turkeys have a role in shedding metabolic heat.

So it's not improbable for some non-avian maniraptors to have had some naked parts of the body, either for display or thermoregulatory purposes, especially the neck. (Feathers in the neck region are genetically easier to lose than feathers elsewhere on the body, which explains why so many different bird lineages have evolved bald necks for various purposes.) In particular, large cursorial non-avian maniraptors that lived in arid environments may well have had an ostrich-like feather covering. Nevertheless, there is little reason to think that any maniraptor lost its feathers to the same degree elephants, hippos, and rhinos have lost their hair. Even in flightless birds with naked skin patches, the rest of the body still tends to be densely feathered. Indeed, wing feathers in aviremigian maniraptors don't have much to do with insulation and may well have been present in even the largest aviremigians. (They wouldn't have gotten in the way of predation. Might talk about that in a later post.) In fact, ostriches and rheas have even more remiges than flying birds because they no longer need to fly. They have remiges on both sides of the arm, while flying birds only have them on the same side as the ulna. Whether or not any extinct maniraptors had similar feather arrangement is unknown.

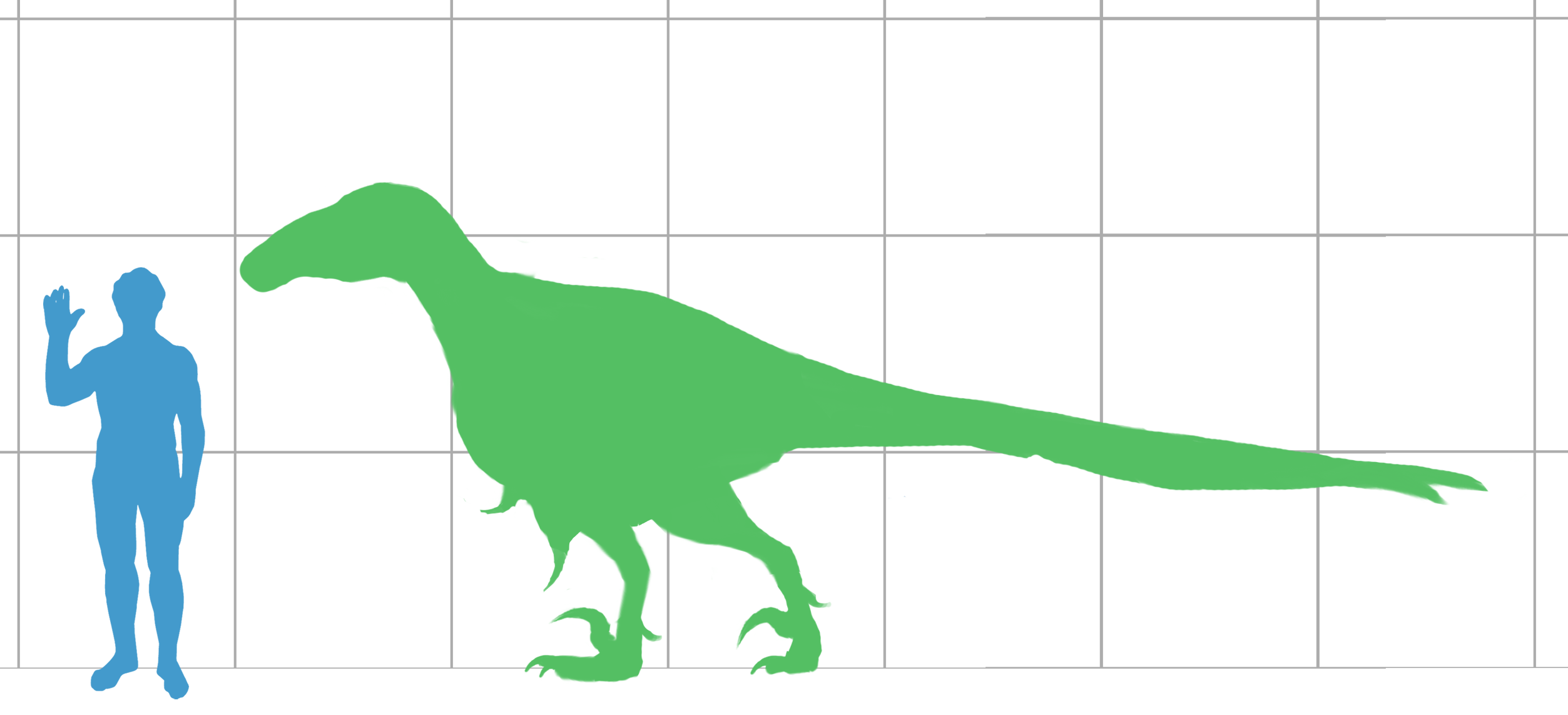

How big is a big maniraptor? Some would say Deinonychus was a "big maniraptor", but truth be told it really... wasn't. Although it was fairly large for a dromaeosaurid, it still wasn't larger than even the largest living maniraptor, the ostrich. A large ostrich can easily weigh more than a hundred kilograms, while Deinonychus has been estimated at around seventy kilograms.

| Size comparison between several large aviremigian maniraptors (and a synapsid) by Matt Martyniuk, from Wikipedia. Notice Deinonychus sulking at the back out of embarrassment from being much smaller than the others. |

There are several dromaeosaurids that were much larger than Deinonychus, however. Achillobator, Austroraptor, and Utahraptor are the largest dromaeosaurids known. Utahraptor has been estimated at five hundred kilograms and seven meters long, and Achillobator and Austroraptor were probably slightly smaller. Some rumored undescribed specimens of Utahraptor are allegedly even larger, but for the sake of simplicity we can probably ignore those for now.

|

| Size comparison between Utahraptor ostrommaysorum (including an alleged undescribed specimen) and a human by Matt Martyniuk, from Wikipedia. |

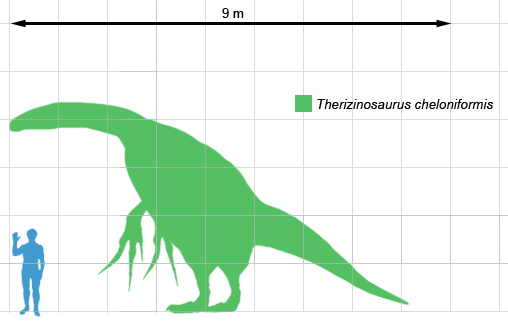

Large as they were, these large dromaeosaurids were dwarfed by several other maniraptors. The oviraptorosaur Gigantoraptor was more than eight meters long and weighed more than a ton. It was about the same size as the tyrannosaurids Albertosaurus and Gorgosaurus. Multiple therizinosaur taxa may have also rivaled or exceeded the biggest dromaeosaurids in mass, including Alxasaurus, Falcarius, Nothronychus, Suzhousaurus, Enigmosaurus, Erlikosaurus, Nanshiungosaurus, and Segnosaurus. The largest known therizinosaur (in fact, the largest known maniraptor) was Therizinosaurus itself. Some estimates put it as being around three meters tall at the hip and weighing as much as six tons. Given the strange, upright build therizinosaurs tended to have, it probably would've been a very imposing animal in life.

|

| Size comparison between Therizinosaurus cheloniformis and a human by Matt Martyniuk, from Wikipedia. |

The concept that large maniraptors may have lost their feathers is based on the fact that several large modern tropical land mammal lineages (such as elephants, rhinos, and hippos) have greatly reduced insulating integument, which sounds reasonable. (It's a bit less reasonable when other types of mammals such as humans, naked mole rats, or whales are brought up, given that their reduction of hair involves specialized lifestyles not known in any maniraptor.) These mammals have dispensed with a thick coat of hair because they are large enough to maintain their body temperature without insulation, and probably because they'd overheat with a typical mammalian coat.

On the other hand, there's reason to think that overheating was not quite as much of a problem for theropods as it is for mammals. For one thing, theropods typically have greater surface to volume ratio than mammals do. After all, Velociraptor was roughly the size of a coyote, but was longer than the average man is tall. Even among mammals, surface area to volume ratio appears to make a difference in determining how much insulating integument is reduced. Giraffes and black rhinos are in the same size range, but giraffes haven't greatly reduced their coats of hair, because their surface area to volume ratio is much greater than that of black rhinos. It's worth noting that the builds of elephants, hippos, and rhinos are all terrible for shedding heat, while this was not the case with theropods. Secondly, theropods have an air sac system that mammals do not, and greatly increases their ability to shed excess heat. Indeed, preliminary calculations by Andrea Cau suggest that not even the tyrannosaurid Tyrannosaurus would've been greatly inconvenienced by a feather coat, and Tyrannosaurus was significantly larger than all known maniraptors, barring Therizinosaurus. I suspect the largest coelurosaur with a coat of plumage of a given thickness would've potentially been larger than the largest mammal with an equally thick hair coat.

Besides, there are other reasons why elephants, hippos, and rhinos don't make ideal comparisons to most big maniraptors. Rumors notwithstanding, Utahraptor, Achillobator, and Austroraptor weren't anywhere close to the size of those big mammals. Modern mammals in their size range, even those in tropical environments, don't show a particularly marked reduction in hair. (Funnily, the largest known avian maniraptors were about as large as the largest dromaeosaurids, but rarely does anyone suggest that they lost their feathers. Such baseless differences between the treatment of non-avian and avian maniraptors is quickly becoming an Overly Long Gag.) That leaves only Gigantoraptor, Nothronychus, Suzhousaurus, Segnosaurus, and Therizinosaurus as the only known maniraptors in the size range of large terrestrial mammals with reduced integument covering. Furthermore, the hair loss in hippos (and likely the ancestors of elephants) may well have as much to do with their semi-aquatic habits as it does with size and build, while there's no evidence that any big maniraptors had semi-aquatic ancestors.

|

| Cartoon of hypothetical dromaeosaurids with lifestyles that may lead to significant reduction of insulating integument. Tellingly, none of them are known to have existed. |

There's more. Feathers, especially pennaceous feathers (which most maniraptors have) are excellent insulators. They prevent both heat loss from the body and overheating caused by ambient heat. We're biased in our typical view of insulation because we deal with high temperatures by sweating, which isn't too effective with thick clothing covering our skin, but in fact, male turkeys are more likely to overheat from high ambient temperatures than female turkeys are because of their bald heads. Even for us, wearing thin clothing that still allows for evaporation of sweat can actually help lower body temperature. That said, feather loss in some areas of the body in maniraptors can be beneficial under some circumstances. For example, ostriches have naked flanks, legs, and inner wings, and rheas have naked legs and inner wings. These birds can run very fast and probably generate a lot of heat doing so, but live in fairly arid environments and can remain active in hot weather. It turns out that the featherless parts of an ostrich or rhea can all be shaded easily by the bird's wings or the rest of the body, so the heat generated during the day is stored and then can be rapidly shed in one go. The bald heads of certain vultures have also been found to be important in thermoregulation (instead of being an adaptation to cope with messy feeding habits; indeed, the messiest vultures don't have the baldest heads, and most vultures have feathered heads). These vultures usually need to cope with rapidly changing temperatures while soaring, and can quickly facilitate or prevent heat loss by extending or retracting the neck. Even the bald heads of turkeys have a role in shedding metabolic heat.

So it's not improbable for some non-avian maniraptors to have had some naked parts of the body, either for display or thermoregulatory purposes, especially the neck. (Feathers in the neck region are genetically easier to lose than feathers elsewhere on the body, which explains why so many different bird lineages have evolved bald necks for various purposes.) In particular, large cursorial non-avian maniraptors that lived in arid environments may well have had an ostrich-like feather covering. Nevertheless, there is little reason to think that any maniraptor lost its feathers to the same degree elephants, hippos, and rhinos have lost their hair. Even in flightless birds with naked skin patches, the rest of the body still tends to be densely feathered. Indeed, wing feathers in aviremigian maniraptors don't have much to do with insulation and may well have been present in even the largest aviremigians. (They wouldn't have gotten in the way of predation. Might talk about that in a later post.) In fact, ostriches and rheas have even more remiges than flying birds because they no longer need to fly. They have remiges on both sides of the arm, while flying birds only have them on the same side as the ulna. Whether or not any extinct maniraptors had similar feather arrangement is unknown.

|

| Restoration of Achillobator giganticus with plausible ostrich-like feather distribution by Matt Martyniuk. Derived dromaeosaurids weren't cursorial, but fulfilling two out of three requirements is close enough! |

Sunday, June 19, 2011

Maniraptor Feathers Part IV: What Good are Feathers?

Another occasional objection that is raised regarding feathered maniraptors is, "Why would taxon A have feathers? It didn't need them!"

Which... isn't really an objection. After all, there is generally no evidence that the taxon concerned "didn't need feathers", even though there may be evidence from phylogenetic inference or even direct fossil evidence that it did have them. Besides, many animals (including many dinosaurs) are known to have some crazy structures for which their function isn't obvious, but that isn't really evidence those animals didn't have them. (Who can actually say, for example, exactly what stegosaur plates or Psittacosaurus bristles were for?) This ends up as more an argument from personal incredulity (i.e.: "I can't think of how taxon A would've used its feathers, so it didn't have any!").

Nevertheless, just as with stegosaur plates and Psittacosaurus bristles, it's still good to try and seek out potential functions for feathers in non-avian maniraptors. Fortunately, the function of feathers is somewhat easier to infer than stegosaur plates or Psittacosaurus bristles, as there are still feathered maniraptors alive today.

All living maniraptors are either flighted or have flighted ancestors, and a primary function of feathers in neornithines is to help them fly. However, no non-avian maniraptor was quite as adapted to flight as modern neornithines, even though some clades have been suggested to have been secondarily flightless and a number of small deinonychosaurs could've had some limited aerial capability. The presence of plumaceous feathers with no aerodynamic qualities in non-maniraptor coelurosaurs with no flight adaptations shows that feathers arose before flight in dinosaurs began to evolve. (That's right, plumaceous feathers were probably present in basal coelurosaurs. Might talk a bit about that later in the series.) As feathers are found in flightless coelurosaurs (including modern ones), they must also be beneficial in other ways. Feathers are exaptations; they were later adapted for flight, but that wasn't their original function.

Another major function of feathers in modern maniraptors (both flighted and flightless) is insulation, and feathers are important in both keeping maniraptors warm in the cold and keeping them cool in the heat. Plumaceous feathers found in basal coelurosaurs (as well as in basal maniraptors such as therizinosaurs and alvarezsauroids) likely had this function.

Many non-avian maniraptors didn't just have plumaceous feathers, however. Oviraptorosaurs and deinonychosaurs are both known have had pennaceous feathers. Pennaceous feathers are also useful for insulation, and asymmetrical pennaceous feathers (which are known in the dromaeosaurid Microraptor) are good for gliding and flying with. In addition, pennaceous feathers are also more useful than plumaceous feathers in visual communication, due to their wider display area and (possibly) greater range of colors that they can show. Some feather structures known in non-avian maniraptors, such as tail fan and the short primary feathers forming little "hand flags" in Caudipteryx zoui and the feather crests in Microraptor and Anchiornis, were likely for display purposes. (In the case of Anchiornis, the feather crest is known to have been orange, in contrast to the dark gray and black of the rest of the animal, which supports its use in visual display. Similarly, the wing feathers of Caudipteryx show a banded color pattern. Furthermore, the development of wing feathers in Similicaudipteryx signify that the wing feathers were more important in older individuals than in younger ones.)

The greater area of pennaceous feathers likely served another purpose, too. Several oviraptorid and troodont specimens have been preserved brooding on top of their nests with the forelimbs extended over the eggs. The wing feathers that were likely present in these taxa would have helped cover the eggs while the dinosaurs were brooding.

Some flightless birds have yet another use for their wings. Rheas and ostriches flick their wings out to the sides while running to help them make quick turns. Cursorial flightless non-avian maniraptors may have done the same.

An interesting idea that's been proposed in the last decade is Wing-Assisted Incline Running (WAIR). Many birds, particularly those that are primarily terrestrial or too young to fly, can escape from predators by flapping their wings to help them run up inclined surfaces such as tree trunks. This behavior was first observed in chukar partidges and has been documented among many neornithine groups. It's been suggested that small non-avian maniraptors with well-developed wing feathers may have also used WAIR and that it contributed to the evolution of flight. Other researchers, however, argue that the restricted forelimb movement in non-avian maniraptors wouldn't have allowed them to perform WAIR. (Non-avian maniraptors couldn't lift the wings above their backs. Indeed, not even confuciusornithids could!)

Which... isn't really an objection. After all, there is generally no evidence that the taxon concerned "didn't need feathers", even though there may be evidence from phylogenetic inference or even direct fossil evidence that it did have them. Besides, many animals (including many dinosaurs) are known to have some crazy structures for which their function isn't obvious, but that isn't really evidence those animals didn't have them. (Who can actually say, for example, exactly what stegosaur plates or Psittacosaurus bristles were for?) This ends up as more an argument from personal incredulity (i.e.: "I can't think of how taxon A would've used its feathers, so it didn't have any!").

Nevertheless, just as with stegosaur plates and Psittacosaurus bristles, it's still good to try and seek out potential functions for feathers in non-avian maniraptors. Fortunately, the function of feathers is somewhat easier to infer than stegosaur plates or Psittacosaurus bristles, as there are still feathered maniraptors alive today.

All living maniraptors are either flighted or have flighted ancestors, and a primary function of feathers in neornithines is to help them fly. However, no non-avian maniraptor was quite as adapted to flight as modern neornithines, even though some clades have been suggested to have been secondarily flightless and a number of small deinonychosaurs could've had some limited aerial capability. The presence of plumaceous feathers with no aerodynamic qualities in non-maniraptor coelurosaurs with no flight adaptations shows that feathers arose before flight in dinosaurs began to evolve. (That's right, plumaceous feathers were probably present in basal coelurosaurs. Might talk a bit about that later in the series.) As feathers are found in flightless coelurosaurs (including modern ones), they must also be beneficial in other ways. Feathers are exaptations; they were later adapted for flight, but that wasn't their original function.

Another major function of feathers in modern maniraptors (both flighted and flightless) is insulation, and feathers are important in both keeping maniraptors warm in the cold and keeping them cool in the heat. Plumaceous feathers found in basal coelurosaurs (as well as in basal maniraptors such as therizinosaurs and alvarezsauroids) likely had this function.

Many non-avian maniraptors didn't just have plumaceous feathers, however. Oviraptorosaurs and deinonychosaurs are both known have had pennaceous feathers. Pennaceous feathers are also useful for insulation, and asymmetrical pennaceous feathers (which are known in the dromaeosaurid Microraptor) are good for gliding and flying with. In addition, pennaceous feathers are also more useful than plumaceous feathers in visual communication, due to their wider display area and (possibly) greater range of colors that they can show. Some feather structures known in non-avian maniraptors, such as tail fan and the short primary feathers forming little "hand flags" in Caudipteryx zoui and the feather crests in Microraptor and Anchiornis, were likely for display purposes. (In the case of Anchiornis, the feather crest is known to have been orange, in contrast to the dark gray and black of the rest of the animal, which supports its use in visual display. Similarly, the wing feathers of Caudipteryx show a banded color pattern. Furthermore, the development of wing feathers in Similicaudipteryx signify that the wing feathers were more important in older individuals than in younger ones.)

| Male Pavo cristatus in display using pennaceous tail feathers photographed by PRA, from Wikipedia. |

The greater area of pennaceous feathers likely served another purpose, too. Several oviraptorid and troodont specimens have been preserved brooding on top of their nests with the forelimbs extended over the eggs. The wing feathers that were likely present in these taxa would have helped cover the eggs while the dinosaurs were brooding.

|

| Fossil of Citipati osmolskae brooding on nest photographed by Matt Martyniuk, from Wikipedia. |

Some flightless birds have yet another use for their wings. Rheas and ostriches flick their wings out to the sides while running to help them make quick turns. Cursorial flightless non-avian maniraptors may have done the same.

An interesting idea that's been proposed in the last decade is Wing-Assisted Incline Running (WAIR). Many birds, particularly those that are primarily terrestrial or too young to fly, can escape from predators by flapping their wings to help them run up inclined surfaces such as tree trunks. This behavior was first observed in chukar partidges and has been documented among many neornithine groups. It's been suggested that small non-avian maniraptors with well-developed wing feathers may have also used WAIR and that it contributed to the evolution of flight. Other researchers, however, argue that the restricted forelimb movement in non-avian maniraptors wouldn't have allowed them to perform WAIR. (Non-avian maniraptors couldn't lift the wings above their backs. Indeed, not even confuciusornithids could!)

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Maniraptor Feathers Part III: The Asian Maniraptors are Not Aberrant

I've seen it casually suggested on occasion that as, to date, direct evidence of feathers has mostly been found in Asian coelurosaurs, coelurosaurs found elsewhere wouldn't have had feathers.

Which is complete crap, of course.

There is no evidence that Asia was somehow different in some way from other parts of the world that would cause maniraptors to have feathers. There's also no evidence that any maniraptor outside of Asia did not have feathers, even though phylogenetic inference predicts that the default assumption should be that all maniraptors have feathers.

Besides, even among only the maniraptors that are known to preserve direct evidence of feathers, they still represent taxa from multiple different formations (some with vastly different paleoenvironments), multiple maniraptor lineages with greatly varying lifestyles, and a time span of 95 million years. There's no indication that these taxa shared anything specific with each other that aren't shared with other maniraptors. And there's also the fact that fossil dinosaurs which preserve evidence of feathers are known from outside of Asia, such as Rahonavis and Juravenator. (And Archaeopteryx, but no one cares because it's a de facto "bird". We again see the recurring theme of differing treatment between de facto "birds" and other types of maniraptors, even though there is no logical basis behind such behavior.)

The fact that extensive scales are known from other dinosaurs outside of Asia means nothing, because these skin impressions represent those from abelisaurids, titanosaurs, carnosaurs, ceratopsians, thyreophorans, and ornithopods, not maniraptors. It's not as though extensive scaly impressions aren't known from Asian dinosaurs: at least one Psittacosaurus specimen from the Yixian preserves scaly skin over most of its body (albeit along with enigmatic bristles on its tail). Tellingly, it's a ceratopsian instead of a maniraptor, showing that phylogenetics is indeed more important in determining integument than arbitrary political and geographic divisions... as it should be. The only reason the Yixian, Jiufotang, and Tiaojishan maniraptors preserve integument is because they were "lucky" enough to die in an environment conductive to soft tissues. Nothing more. Other Mesozoic dinosaurs must rely on the occasional skin impression or badly preserved integument (as in Shuvuuia), or subtle skeletal features such as quill knobs (which may not be immediately obvious; it took more than eighty years for them to be identified in Velociraptor, after all) if direct evidence of their integument is to be obtained. As far as we can tell, the presence of integument on a given taxon has nothing to do with location.

The notion that only Asian non-avian maniraptors had feathers has so many giant holes in it one could fly a Pelagornis through it. It is evidently just another example of desperate wishful thinking, although clearly not much "thinking" has been put into it.

Which is complete crap, of course.

There is no evidence that Asia was somehow different in some way from other parts of the world that would cause maniraptors to have feathers. There's also no evidence that any maniraptor outside of Asia did not have feathers, even though phylogenetic inference predicts that the default assumption should be that all maniraptors have feathers.

Besides, even among only the maniraptors that are known to preserve direct evidence of feathers, they still represent taxa from multiple different formations (some with vastly different paleoenvironments), multiple maniraptor lineages with greatly varying lifestyles, and a time span of 95 million years. There's no indication that these taxa shared anything specific with each other that aren't shared with other maniraptors. And there's also the fact that fossil dinosaurs which preserve evidence of feathers are known from outside of Asia, such as Rahonavis and Juravenator. (And Archaeopteryx, but no one cares because it's a de facto "bird". We again see the recurring theme of differing treatment between de facto "birds" and other types of maniraptors, even though there is no logical basis behind such behavior.)

The fact that extensive scales are known from other dinosaurs outside of Asia means nothing, because these skin impressions represent those from abelisaurids, titanosaurs, carnosaurs, ceratopsians, thyreophorans, and ornithopods, not maniraptors. It's not as though extensive scaly impressions aren't known from Asian dinosaurs: at least one Psittacosaurus specimen from the Yixian preserves scaly skin over most of its body (albeit along with enigmatic bristles on its tail). Tellingly, it's a ceratopsian instead of a maniraptor, showing that phylogenetics is indeed more important in determining integument than arbitrary political and geographic divisions... as it should be. The only reason the Yixian, Jiufotang, and Tiaojishan maniraptors preserve integument is because they were "lucky" enough to die in an environment conductive to soft tissues. Nothing more. Other Mesozoic dinosaurs must rely on the occasional skin impression or badly preserved integument (as in Shuvuuia), or subtle skeletal features such as quill knobs (which may not be immediately obvious; it took more than eighty years for them to be identified in Velociraptor, after all) if direct evidence of their integument is to be obtained. As far as we can tell, the presence of integument on a given taxon has nothing to do with location.

The notion that only Asian non-avian maniraptors had feathers has so many giant holes in it one could fly a Pelagornis through it. It is evidently just another example of desperate wishful thinking, although clearly not much "thinking" has been put into it.

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Maniraptor Feathers Part II: Phylogenetic Inference

As discussed in the previous post, there is direct evidence of feathers in multiple non-avian maniraptors. But we can also be quite confident in saying that other maniraptors for which we don't have integument also had feathers as well. How do we know?

The same way we know (as in, be quite certain) that extinct mammals without integument preserved very likely had fur: through phylogenetic inference.

We know that closely related organisms tend to be more similar to each other than to more distantly related ones because they share more characteristics with one another. With this in mind, we can often infer whether or not a characteristic is present in a fossil organism if we have enough data on its close relatives, even if we don't have direct evidence of that organism possessing or lacking said characteristic.

For example, we don't have the hands of Tsaagan, so, strictly speaking, we can't directly tell how many fingers it had. However, we do have the hands of its close relatives, and when we reconstruct the relationships between it and its relatives, we can see that both its closest known relative (Linheraptor) and its close-but-not-as-close relatives (such as Velociraptor) are both known to have had three-fingered hands. Therefore, we can infer that Tsaagan likely also had three-fingered hands.

We can do the same thing when trying to figure out what kind of integument maniraptors (or mammals, or lizards, etc.) that haven't preserved any direct evidence of their skin coverings had.

We don't yet have any unequivocal direct evidence of what kind of integument Deinonychus had, for example. However, its phylogenetic position shows that it's nested deep within a clade of known feathered dinosaurs. Some of these feathered dinosaurs are fairly close relatives of Deinonychus (such as Velociraptor or Microraptor). Perhaps more importantly, none of the members of this clade are known to have had any integument other than extensive feathering. (Most do have scales, but only on limited areas of the body such as the feet.) Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that Deinonychus also had feathers.

If this conclusion somehow sounds "shaky", it shouldn't be. At least, it shouldn't be any more shaky than the conclusion that Dinofelis likely had fur because it's nested deep within a clade of furry animals, or that Hesperornis had feathers because it's also nested deep within a clade of feathered animals. No one ever questions those because... I honestly don't know. In fact, such inference has already accurately predicted the presence of feathers in at least one case, Velociraptor. Even before quill knobs were discovered on Velociraptor in 2007, phylogenetic inference showed that Velociraptor likely had feathers.

Some "critics" of phylogenetic inference like to use the example of a modern elephant and a mammoth to show how "unreliable" this method is. If modern elephants were extinct and we only knew about the integument of mammoths, so the claim goes, phylogenetic inference would turn out to be completely wrong because it would lead us to think that modern elephants had fur. But, actually, that prediction would turn out to be entirely right!

That said, we wouldn't necessarily be able to predict accurately that modern elephants would have had such a sparse covering of hair. But we know from the anatomy of modern animals that even though the arrangement of integument can vary greatly based on environmental factors as well as sexual selection, the presence of integument is not nearly as variable. So we may not be able to tell exactly what the feathers of Deinonychus were like, but we can quite safely say that it did indeed have feathers, as well as infer some more general patterns.

Of course, phylogenetics doesn't always work. For example, the velociraptorine dromaeosaurid Balaur had two fingers instead of three. Had the hands of Balaur not been discovered, we might have thought it had three fingers. However, such examples would clearly be in the minority. For one two-fingered dromaeosaurid taxon there are dozens of three-fingered dromaeosaurid (and other avetheropod) taxa which would have had their finger count predicted accurately by the same method.

Is it technically possible that a maniraptor taxon had scales or fur or pycnofibers or tentacles or cornflakes covering most of their skin instead of feathers? I'll have to confess that, yes, it's technically possible, against all odds. But science doesn't care about what is technically possible. Is there evidence for these possibilities? No. So, until evidence in their favor is found, we can stop kidding ourselves that those possibilities are more likely than (or as likely as) an alternative for which we do have evidence: all maniraptors likely had feathers.

Is that too bold? Really? Any more bold than saying that all extinct mammals likely had fur or that all avian maniraptors likely had feathers?

The same way we know (as in, be quite certain) that extinct mammals without integument preserved very likely had fur: through phylogenetic inference.

We know that closely related organisms tend to be more similar to each other than to more distantly related ones because they share more characteristics with one another. With this in mind, we can often infer whether or not a characteristic is present in a fossil organism if we have enough data on its close relatives, even if we don't have direct evidence of that organism possessing or lacking said characteristic.

For example, we don't have the hands of Tsaagan, so, strictly speaking, we can't directly tell how many fingers it had. However, we do have the hands of its close relatives, and when we reconstruct the relationships between it and its relatives, we can see that both its closest known relative (Linheraptor) and its close-but-not-as-close relatives (such as Velociraptor) are both known to have had three-fingered hands. Therefore, we can infer that Tsaagan likely also had three-fingered hands.

We can do the same thing when trying to figure out what kind of integument maniraptors (or mammals, or lizards, etc.) that haven't preserved any direct evidence of their skin coverings had.

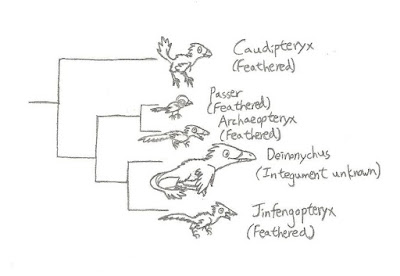

We don't yet have any unequivocal direct evidence of what kind of integument Deinonychus had, for example. However, its phylogenetic position shows that it's nested deep within a clade of known feathered dinosaurs. Some of these feathered dinosaurs are fairly close relatives of Deinonychus (such as Velociraptor or Microraptor). Perhaps more importantly, none of the members of this clade are known to have had any integument other than extensive feathering. (Most do have scales, but only on limited areas of the body such as the feet.) Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that Deinonychus also had feathers.

|

| Simplified cladogram of Maniraptora using the Raptormaniacs cast. |

If this conclusion somehow sounds "shaky", it shouldn't be. At least, it shouldn't be any more shaky than the conclusion that Dinofelis likely had fur because it's nested deep within a clade of furry animals, or that Hesperornis had feathers because it's also nested deep within a clade of feathered animals. No one ever questions those because... I honestly don't know. In fact, such inference has already accurately predicted the presence of feathers in at least one case, Velociraptor. Even before quill knobs were discovered on Velociraptor in 2007, phylogenetic inference showed that Velociraptor likely had feathers.

Some "critics" of phylogenetic inference like to use the example of a modern elephant and a mammoth to show how "unreliable" this method is. If modern elephants were extinct and we only knew about the integument of mammoths, so the claim goes, phylogenetic inference would turn out to be completely wrong because it would lead us to think that modern elephants had fur. But, actually, that prediction would turn out to be entirely right!

|

| Close up of an Asian elephant's eye showing integument (including specialized hair) photographed by Alexander Klink, from Wikipedia. |

That said, we wouldn't necessarily be able to predict accurately that modern elephants would have had such a sparse covering of hair. But we know from the anatomy of modern animals that even though the arrangement of integument can vary greatly based on environmental factors as well as sexual selection, the presence of integument is not nearly as variable. So we may not be able to tell exactly what the feathers of Deinonychus were like, but we can quite safely say that it did indeed have feathers, as well as infer some more general patterns.

Of course, phylogenetics doesn't always work. For example, the velociraptorine dromaeosaurid Balaur had two fingers instead of three. Had the hands of Balaur not been discovered, we might have thought it had three fingers. However, such examples would clearly be in the minority. For one two-fingered dromaeosaurid taxon there are dozens of three-fingered dromaeosaurid (and other avetheropod) taxa which would have had their finger count predicted accurately by the same method.

Is it technically possible that a maniraptor taxon had scales or fur or pycnofibers or tentacles or cornflakes covering most of their skin instead of feathers? I'll have to confess that, yes, it's technically possible, against all odds. But science doesn't care about what is technically possible. Is there evidence for these possibilities? No. So, until evidence in their favor is found, we can stop kidding ourselves that those possibilities are more likely than (or as likely as) an alternative for which we do have evidence: all maniraptors likely had feathers.

Is that too bold? Really? Any more bold than saying that all extinct mammals likely had fur or that all avian maniraptors likely had feathers?

Monday, June 13, 2011

Back to the basics - Maniraptor Feathers Part I: The Fossil Evidence

Because drawing comics is getting to be rather time consuming and difficult to do regularly, I'm taking this blog in a more informative direction. I could talk about some really interesting and semi-obscure stuff, but there are other blogs around that discuss maniraptors now and then and do it far better than I'd be able to, and I'd mostly be reciting things that I've learned from those blogs if I did. I will be discussing topics far too basic and petty for more competent bloggers to cover, starting with the ever-present controversy-that-is-not-really-a-controversy-at-all: did non-avian maniraptors have feathers? (Incidentally, I'm not abandoning the comic entirely. I'll probably still slip in a few strips or pages from time to time, or use the characters to illustrate posts.)

The simple answer to this, as every dinosaur enthusiast knows by now, is yes. Non-avian maniraptors did have feathers. There's no question about it. To say that there's more than enough evidence for this is an understatement. The most direct evidence, of course, is fossil evidence, and we have mountains of fossil evidence for feathers in non-avian maniraptors. It's a wonder that we do, given that soft tissues rarely fossilize. However, some formations, such as the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation and Jiufotang Formation and the Late Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation in China, often do preserve soft tissues, including integumentary structures, in exquisite detail, making them veritable treasure troves for paleontologists. Several maniraptor taxa have been found in such deposits, many of them preserving feathers. In some cases it is also possible to infer the presence of feathers through skeletal features. To date, at least fifteen non-avialian maniraptors have been preserved with direct evidence of feathers. (I'm not including avialians simply because no one ever has any problem with them being feathered for... reasons, I guess. Even though many of them are preserved in the exact same deposits as non-avialian maniraptors. I don't understand it either.)

Avimimus (1987)

That's right, there was direct evidence of feathered non-avialian maniraptors before the 1990s! In 1987, Kuzanov (the original describer of Avimimus) reported the presence of a ridge on the ulna of this oviraptorosaur, indicating the presence of secondary feathers (wing feathers on the ulna). Evidently that wasn't convincing enough at the time and this has since been often overlooked.

Protarchaeopteryx (1997)

Though first thought to be an archaeopterygid avialian, this has since turned out to be a basal oviraptorosaur. Though the holotype isn't quite as beautifully preserved as other Yixian fossils, it does preserve large symmetrical pennaceous feathers forming a tail fan on this maniraptor. (There are several main types of feathers. Pennaceous feathers are the vaned feathers we typically see in modern birds. Plumaceous feathers are essentially down. Protofeathers are primitive filaments that can either be single filaments or multiple filaments stemming from the same follicle. All three types are known in non-avian maniraptors.)

Caudipteryx (1998)

Unlike Protarchaeopteryx, this basal oviraptorosaur is known from several good specimens. It also preserves a tail fan, as well as protofeathers on the body and primary feathers (wing feathers attaching to the second finger). Interestingly, it appears that Caudipteryx zoui didn't have secondary feathers, while Caudipteryx dongi did.

Rahonavis (1998)

Rahonavis gets the prize for the first dromaeosaurid found to show evidence of feathers. It's another non-avian maniraptor that was, at first, mistaken for an archaeopterygid avialian. Rahonavis preserved quill knobs on its ulna. Quill knobs anchor the secondary feathers in many modern birds (particularly in strong fliers), and likely served the same purpose in Rahonavis.

Shuvuuia (1999)

One specimen of the alvarezsaurid Shuvuuia came with the remnants of preserved feathers. Unlike other extinct maniraptors for which feathers have been found, it came from the Djadochta Formation in Mongolia, a formation that, although the origin of many excellent fossils, is not known for preservation of soft tissues, and as a consequence only some poorly-preserved protofeathers are present. However, this specimen is still significant in that its feathers have been subject to chemical analysis that show they contain (and lack) the same proteins as modern bird feathers do.

Sinornithosaurus (1999)

Rahonavis may have gotten the prize for the first dromaeosaurid to show evidence of feathers, but Sinornithosaurus gets the honor for the first dromaeosaurid to actually have its feathers preserved. Specimens of Sinornithosaurus have plumaceous feathers all over the body, but truth be told I'm a little fuzzy on the details of the plumage of Sinornithosaurus proper and someone will have to fill me in, particularly as most descriptions of Sinornithosaurus plumage also include information from from the specimen NGMC 91 "Dave", which was considered a possible juvenile Sinornithosaurus at one point but is probably a distinct taxon.

Beipiaosaurus (1999)

For those keeping track, at this point we have four major groups of maniraptors with evidence of feathers: avialians (of course), oviraptorosaurs (Avimimus, Protarchaeopteryx, and Caudipteryx), dromaeosaurids (Rahonavis and Sinornithosaurus), and alvarezsaurids (Shuvuuia). With the discovery of Beipiaosaurus, the therizinosaurs join their ranks. The first specimen of Beipiaosaurus found had thick, shaggy protofeathers on its body, but subsequent, better preserved specimens showed something else surprising: long bristle-shaped feathers on at least the neck and tail forming a second coat underneath the protofeathers. These bristle-shaped protofeathers were given the name Elongated Broad Filamentous Feathers (EBFFs). They may be unique to therizinosaurs, but possible EBFFs have been identified in some yet-to-be-described basal coelurosaur taxa.

Microraptor (2000)

In 1999 a supposed new feathered dinosaur known as "Archaeoraptor" garnered some media attention, but was soon revealed to be a hoax after it was examined by professionals. "Archaeoraptor" was a chimera comprising the upper half of the Mesozoic bird Yanornis and the lower half of a then-undescribed dromaeosaurid. About a year later, that dromaeosaurid became known as Microraptor. Newer specimens of Microraptor preserve a surprising feature: Microraptor had four wings. It had feathers all over its body, including very long wing feathers on its arms and hands and a tail fan on the tip of its tail. This pattern was not unlike other feathered maniraptors known at this point, but Microraptor also had long pennaceous feathers on its legs going down onto the feet. These large wings suggest that Microraptor was capable of some form of aerial locomotion, but exactly how it flew is still debated. Long leg feathers are now also known in several Mesozoic avialians (including Archaeopteryx) and troodonts, but none of theirs are quite as extensive as those of Microraptor.

Nomingia (2000)

Only known from the posterior half of its body, the oviraptorosaur Nomingia had a mass of fused vertebrae on the tip of its tail. This feature, known as a pygostyle, is also known in modern birds (as well as in Beipiaosaurus), and typically supports a fan of feathers. It likely served the same function in Nomingia.

NGMC 91 (2001)

Not yet officially named, this well-preserved dromaeosaurid specimen was described in 2001 and was nicknamed "Dave". Though initially thought to be a juvenile Sinornithosaurus, newer phylogenetic analyses find it a closer relative of Microraptor. It preserves plumaceous feathers all over the body (except for the toes, which have scales, similar to modern birds), and its wing feathers are probably badly preserved pennaceous feathers. It also preserves a tail fan on the tip of the tail.

Yixianosaurus (2003)

Only known from arms and some ribs, Yixianosaurus preserves some feathers, but their exact structure is difficult to tell. It is also hard to say what kind of maniraptor Yixianosaurus was, though its long hands might suggest an affinity with scansoriopterygids, small climbing possible avialians from the Jurassic.

Jinfengopteryx (2005)

Once thought to be an archaeopterygid (again; this is turning into a sort of running gag, which, considering the similarities between archaeopterygids and deinonychosaurs, shouldn't be surprising), this is really the first troodont to preserve feathers. As the wings are tightly folded against the body, the wing feathers are impossible to decipher, but it does preserve body feathers and retrices (long tail feathers) along the length of its tail (as opposed to a tail fan at the tip as in known dromaeosaurids and oviraptorosaurs).

Velociraptor (2007)

In 2007 the famous Velociraptor also entered the ranks of non-avian maniraptors with direct evidence of feathers, this time due to quill knobs on the ulna (similarly to Rahonavis). This was also evidence that medium-sized flightless dromaeosaurids retained large wings, and some have used it to support the idea that deinonychosaurs were secondarily flightless (as quill knobs are found mostly in strong-flying birds). Those who have examined other Velociraptor specimens personally have confirmed that these quill knobs are not aberrations or artifacts of preservation in one particular specimen, and are present on multiple other Velociraptor specimens.

Similicaudipteryx (2008)

When first described in 2008, the presence of a pygostyle in this oviraptorosaur suggested that it had a tail fan. In fact, this was a triumph of sorts for skeletal inference of feathers because when, in 2010, new specimens were found that did indeed preserve actual feathers, lo and behold, they had tail fans (as well as primary and secondary feathers and body feathers). The other interesting thing about these specimens was that they represented different growth stages, and the younger specimen had ribbon-shaped wing feathers (with barbules only at the tips of the feathers) instead of regular pennaceous feathers as in adults. (On the other hand, the "ribbon-shaped feathers" are also similar to the feathers of young birds that are molting, and this might have been the case with the young Similicaudipteryx.) The younger specimen also lacked secondary feathers.

Anchiornis (2009)

This is another troodont that was once thought to be an archaeopterygid. (What did I tell you? It's a running gag.) Although the original specimen preserved feathers, new specimens revealed even more information (as usual). Anchiornis was more heavily feathered than even most modern birds! It was completely feathered down to the toes, the only naked region being the very, very tip of the snout (which unfortunately rarely ever gets taken into account in many reconstructions of this taxon). Anchiornis also showed that, like basal dromaeosaurids (such as Microraptor) and many Mesozoic avialians, troodonts started out with long leg feathers. (Jinfengopteryx doesn't preserve long leg feathers, although allegedly there are some undescribed Yixian troodonts that do.) Furthermore, it was also important in that it was a Jurassic non-avialian maniraptor, showing that there were indeed feathered non-avialian dinosaurs before the existence of Archaeopteryx. (Not that it actually mattered before, but it was good to get confirmation.) Finally, Anchiornis also gets the honor of being the first Mesozoic dinosaur for which we can be quite certain how it looked like in life, as it was the first to get the color pigments preserved in its feathers completely analyzed!

In addition to these, several oviraptorids have been preserved brooding on their nests in postures that suggest they had large wing feathers to cover their eggs. A flange on the second finger of Deinonychus (also found in Sinornithosaurus) has also been suggested online to be an anchor for primary feathers.

Note that even the BAND (Birds Are Not Dinosaurs fringe group) do not deny that maniraptors have feathers, in spite of their great skill in ignoring all evidence and the fact that they've tried (and failed) to discredit the presence of feathers in other coelurosaur groups, so anyone who denies all this fossil evidence is essentially out of luck. (They instead proclaim that all maniraptors are "birds and not dinosaurs". Still not correct, but it's something.)

Some people out there desperately write off the growing evidence as being "fake", but this is flat out wrong on so many levels. Nearly all of these fossils have been studied by many different professionals (including BANDits), and many of these taxa (such as Microraptor, Caudipteryx, and Anchiornis) are known from multiple (sometimes hundreds) of specimens that all preserve feathers. Even the "Archaeoraptor" hoax was quickly exposed after actual scientists studied it, and note that the feathers in neither specimen that was used to composite the hoax were faked. The specimen itself was a hoax, but the feathers were not. Funnily enough, no one has the slightest problem with the mammals that preserve fur and avialian dinosaurs that preserve feathers from the same formations. Nice double standard there.

The simple answer to this, as every dinosaur enthusiast knows by now, is yes. Non-avian maniraptors did have feathers. There's no question about it. To say that there's more than enough evidence for this is an understatement. The most direct evidence, of course, is fossil evidence, and we have mountains of fossil evidence for feathers in non-avian maniraptors. It's a wonder that we do, given that soft tissues rarely fossilize. However, some formations, such as the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation and Jiufotang Formation and the Late Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation in China, often do preserve soft tissues, including integumentary structures, in exquisite detail, making them veritable treasure troves for paleontologists. Several maniraptor taxa have been found in such deposits, many of them preserving feathers. In some cases it is also possible to infer the presence of feathers through skeletal features. To date, at least fifteen non-avialian maniraptors have been preserved with direct evidence of feathers. (I'm not including avialians simply because no one ever has any problem with them being feathered for... reasons, I guess. Even though many of them are preserved in the exact same deposits as non-avialian maniraptors. I don't understand it either.)

Avimimus (1987)

That's right, there was direct evidence of feathered non-avialian maniraptors before the 1990s! In 1987, Kuzanov (the original describer of Avimimus) reported the presence of a ridge on the ulna of this oviraptorosaur, indicating the presence of secondary feathers (wing feathers on the ulna). Evidently that wasn't convincing enough at the time and this has since been often overlooked.

Protarchaeopteryx (1997)

|

| Fossil of Protarchaeopteryx robusta, from Qiang et al., 1998. |

Though first thought to be an archaeopterygid avialian, this has since turned out to be a basal oviraptorosaur. Though the holotype isn't quite as beautifully preserved as other Yixian fossils, it does preserve large symmetrical pennaceous feathers forming a tail fan on this maniraptor. (There are several main types of feathers. Pennaceous feathers are the vaned feathers we typically see in modern birds. Plumaceous feathers are essentially down. Protofeathers are primitive filaments that can either be single filaments or multiple filaments stemming from the same follicle. All three types are known in non-avian maniraptors.)

Caudipteryx (1998)

| Fossil of Caudipteryx zoui photographed by Laikayiu, from Wikipedia. |

Unlike Protarchaeopteryx, this basal oviraptorosaur is known from several good specimens. It also preserves a tail fan, as well as protofeathers on the body and primary feathers (wing feathers attaching to the second finger). Interestingly, it appears that Caudipteryx zoui didn't have secondary feathers, while Caudipteryx dongi did.

Rahonavis (1998)

|

| Fossilized quill knobs in Rahonavis ostromi, from Forster et al., 1998. |

Rahonavis gets the prize for the first dromaeosaurid found to show evidence of feathers. It's another non-avian maniraptor that was, at first, mistaken for an archaeopterygid avialian. Rahonavis preserved quill knobs on its ulna. Quill knobs anchor the secondary feathers in many modern birds (particularly in strong fliers), and likely served the same purpose in Rahonavis.

Shuvuuia (1999)

One specimen of the alvarezsaurid Shuvuuia came with the remnants of preserved feathers. Unlike other extinct maniraptors for which feathers have been found, it came from the Djadochta Formation in Mongolia, a formation that, although the origin of many excellent fossils, is not known for preservation of soft tissues, and as a consequence only some poorly-preserved protofeathers are present. However, this specimen is still significant in that its feathers have been subject to chemical analysis that show they contain (and lack) the same proteins as modern bird feathers do.

Sinornithosaurus (1999)

| Fossil of Sinornithosaurus millenii photographed by Laikayiu, from Wikipedia. |

Rahonavis may have gotten the prize for the first dromaeosaurid to show evidence of feathers, but Sinornithosaurus gets the honor for the first dromaeosaurid to actually have its feathers preserved. Specimens of Sinornithosaurus have plumaceous feathers all over the body, but truth be told I'm a little fuzzy on the details of the plumage of Sinornithosaurus proper and someone will have to fill me in, particularly as most descriptions of Sinornithosaurus plumage also include information from from the specimen NGMC 91 "Dave", which was considered a possible juvenile Sinornithosaurus at one point but is probably a distinct taxon.

Beipiaosaurus (1999)

|

| Fossils of Beipiaosaurus inexpectus from Xu et al., 2009. |